In Burundi, the dominant narrative of the country’s troubled past is overwhelmingly shaped by the Hutu-Tutsi divide, leaving little room for other groups—most notably the Swahili-speaking communities—to claim their place in the national memory.

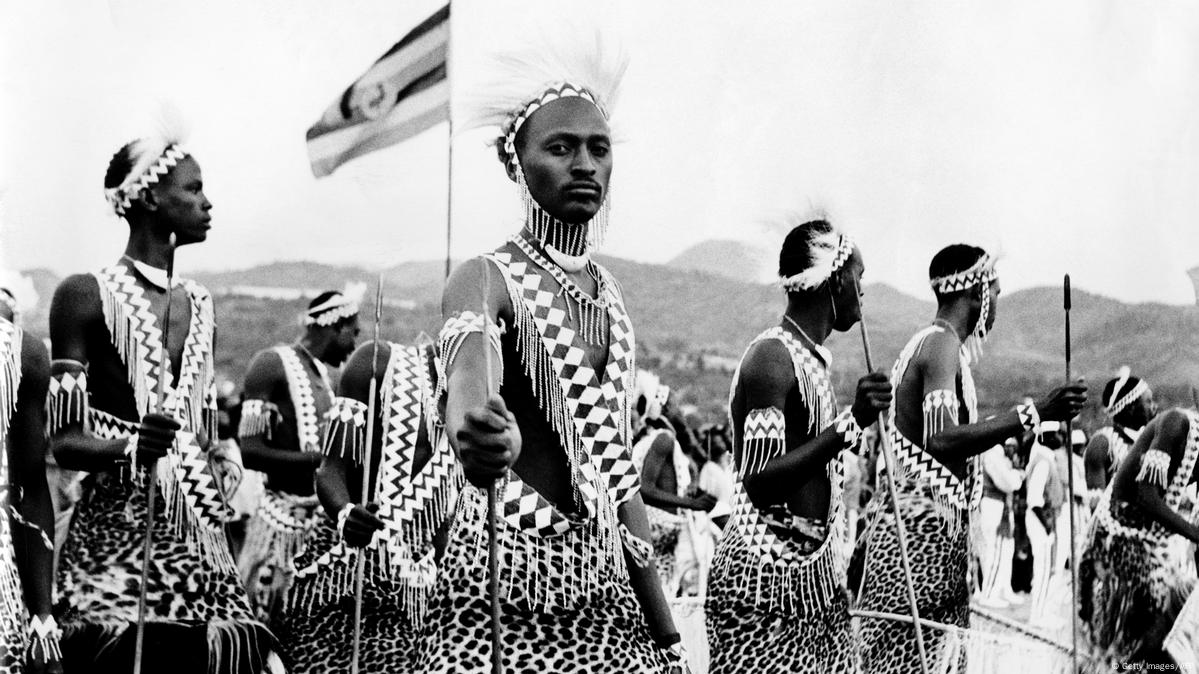

Despite their significant contributions to Burundi’s cultural heritage and independence struggle, Swahili speakers remain largely marginalised in discussions about the country’s history.

Concentrated mainly in urban districts like Buyenzi and Bwiza in Bujumbura, as well as other towns linked to cross-border trade and the Muslim faith, these communities have played pivotal roles in shaping Burundi’s identity.

Yet their voice is often muted, overshadowed by entrenched ethnic dichotomies.

The term “Swahili” carries a complex and sometimes contradictory meaning in Burundi. While some recognise it as a symbol of a rich cultural and linguistic heritage tied to trade and Islam, others harbour stereotypes—portraying Swahili speakers as cunning or untrustworthy, a perception reinforced by similar views from neighbouring Kenya and Tanzania.

This ambivalence contributes to systemic marginalisation, as Swahili speakers are frequently viewed as “non-indigenous” in a nation divided along Hutu and Tutsi lines.

Historically, Swahili-speaking communities were instrumental in Burundi’s independence movement, acting as cultural and political bridges to Pan-Africanist leaders such as Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere.

However, post-independence regimes sidelined them, denying political power and cultural recognition.

Only after the 2005 elections did modest efforts emerge to acknowledge their identity, including the recognition of major Muslim holidays as national public holidays.

Yet, the 2014 law granting Kiswahili regional—but unofficial—status illustrates the limited scope of this recognition.

Swahili speakers often feel compelled to assimilate into dominant social groups for acceptance, a reality fiercely resisted by many within the community.

Ironically, this marginalisation has transformed Swahili-speaking neighbourhoods into enclaves of resilience and neutrality during Burundi’s violent crises—sanctuaries where many sought refuge from persecution.

This resilience underscores the need for inclusive national dialogue that embraces Burundi’s full cultural mosaic.

For Burundi to move forward, it is crucial to integrate Swahili-speaking communities fully into the national conversation.

Their stories deserve to be heard not only on radio and television but also within the halls of political power. Only then can these once-forgotten voices become active agents shaping the nation’s future.