Washington has lifted visa restrictions on Ghana, restoring five-year multiple-entry visas for Ghanaian citizens. But the move comes amid growing criticism over a parallel arrangement that has turned Ghana into a key transit hub for deportations under President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown.

Since early September, at least 14 West African nationals have been expelled from the United States and rerouted through Ghana. The group included men from Nigeria, Mali, Togo, Liberia and Gambia, some of whom reportedly endured the 16-hour flight in “straightjackets.” None had direct ties to Ghana.

The Trump administration has described the practice as “third-country deportations,” a mechanism designed to bypass legal barriers that prevent the direct return of some migrants to their countries of origin.

A federal judge has accused the administration of “circumventing” US court orders that had granted certain individuals protection against deportation.

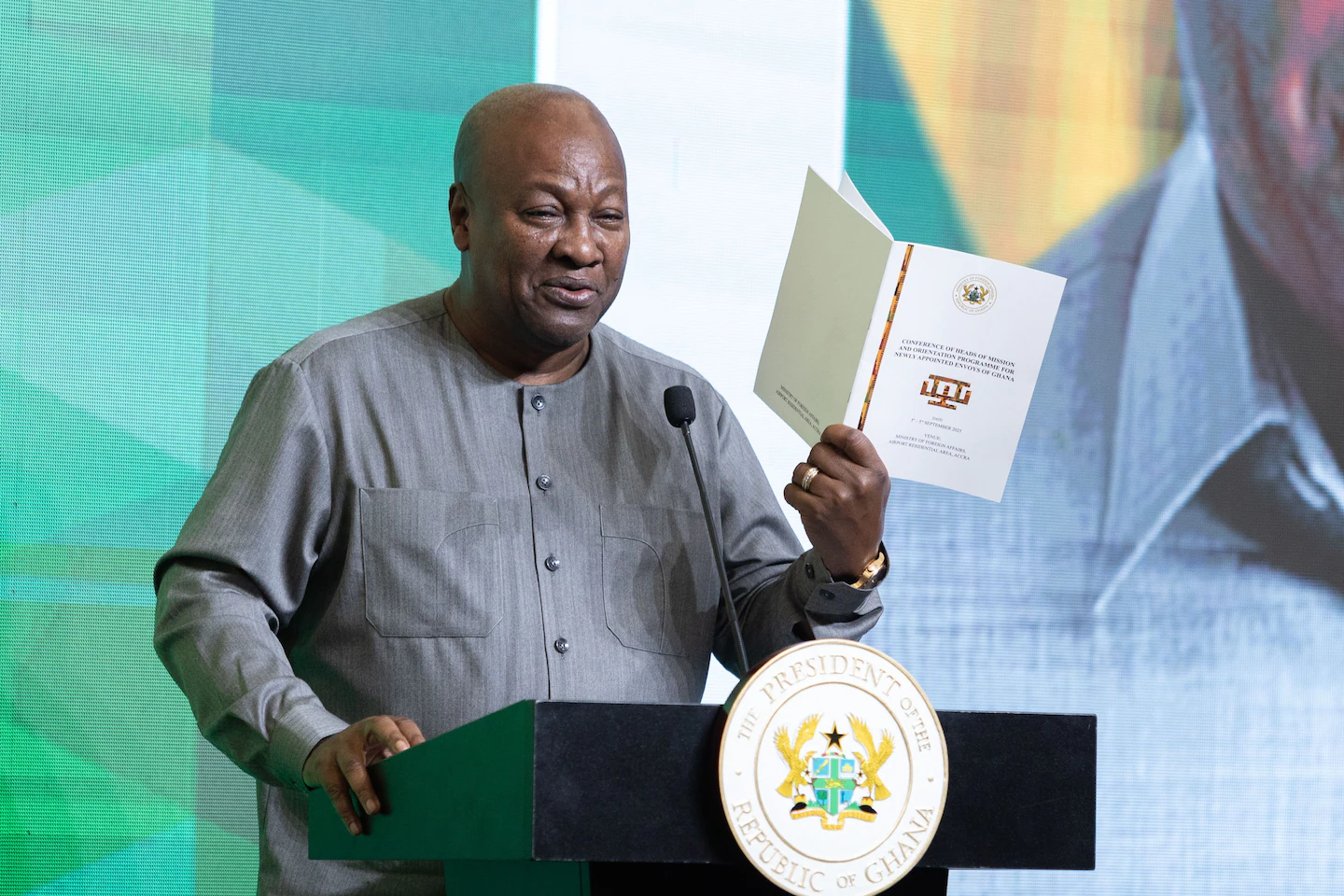

Ghana’s Foreign Minister Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa sought to downplay the controversy, insisting that his country accepted deportees “solely for humanitarian reasons” and received no financial compensation from Washington.

Yet the near-simultaneous lifting of visa restrictions has fuelled speculation of a diplomatic quid pro quo.

Lawyers for the migrants say the policy has inflicted severe consequences.

At least six deportees have already been sent on to Togo, despite having obtained protection in US immigration courts. Others face persecution in their home countries. One Gambian deportee, who identifies as bisexual, fears for his safety in a nation where homosexuality is criminalised.

The cooperation marks a striking reversal in Ghana-US relations. Just three months ago, Ghana was among several African nations hit with sweeping US visa restrictions, with student and business travellers limited to three-month single-entry permits. Washington justified the move by pointing to a 21% student visa overstay rate, well above the 15% threshold considered acceptable.

Observers say Ghana now joins countries such as Rwanda, Eswatini and South Sudan in serving as testing grounds for new migration outsourcing arrangements. Rights advocates warn that the deal sets a dangerous precedent, with short-term diplomatic gains overshadowed by the human cost for those caught in the system.