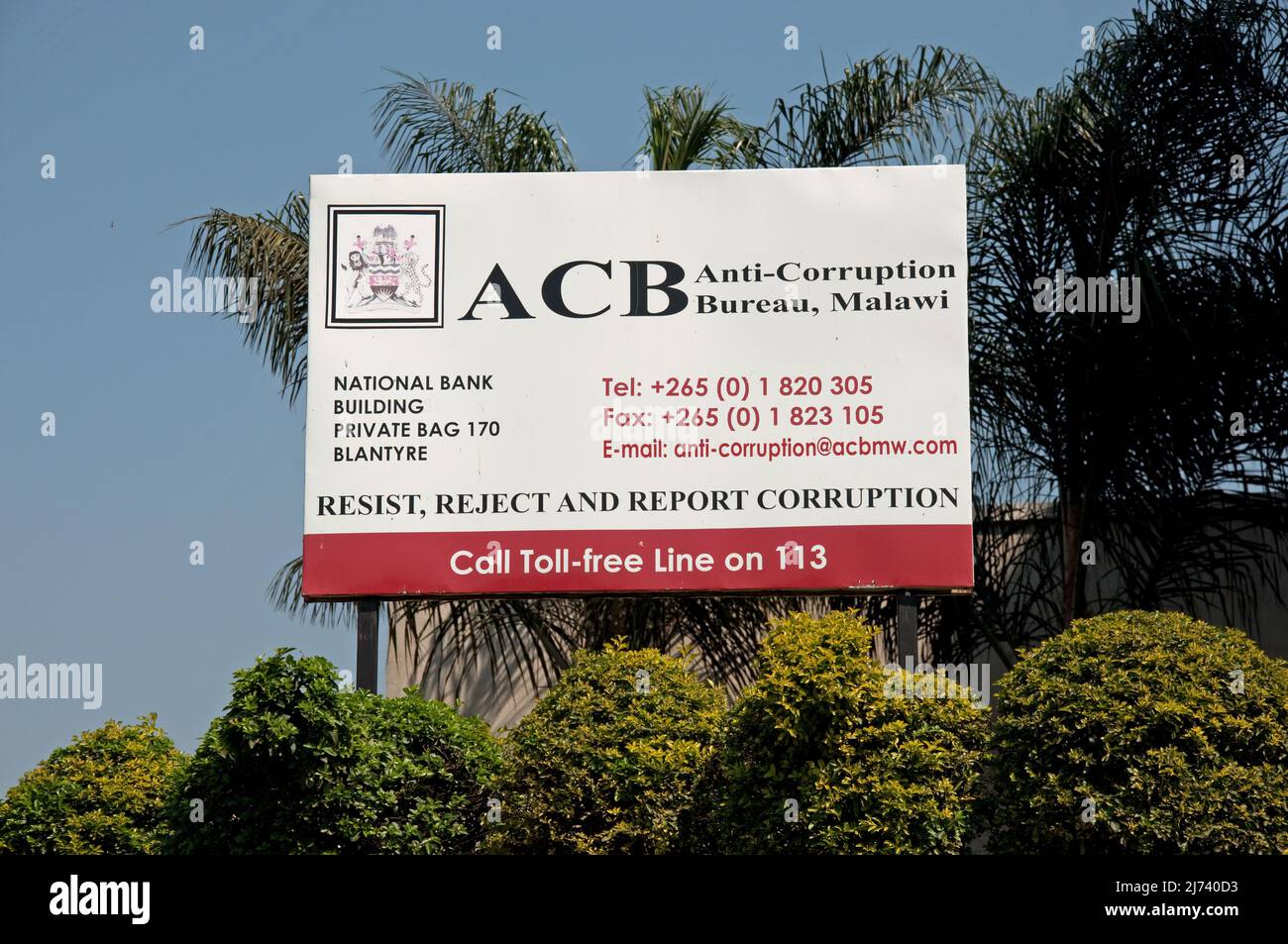

For years, Malawi’s Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) has positioned itself as the nation’s frontline defender against graft. Yet, according to political commentator Suleman Chitera, its focus on rural “sensitization campaigns” is misguided and ultimately insulting to the Malawian people.

Chitera, based in Chiradzulu, highlights a troubling pattern: ACB officials frequently travel to remote villages, using loudspeakers or community gatherings under trees to warn locals about corruption.

These efforts consume considerable resources—fuel, allowances, and accommodation—but the question remains: why concentrate so heavily on rural areas where corruption’s impact is relatively minimal?

“Corruption is not a rural phenomenon,” Chitera asserts. “Villagers are not the ones awarding inflated contracts, looting public funds, or diverting billions from health and education budgets.” Instead, he points fingers at government ministers, CEOs, principal secretaries, and other top officials whose actions cripple Malawi’s development.

The paradox, Chitera argues, is stark: tip off the ACB about a powerful minister engaged in shady dealings and the bureau remains silent; yet a village chief receiving a modest gift sparks immediate investigation. This misplaced priority, he insists, turns the ACB’s campaigns into costly spectacles that fail to address the true scale of corruption.

“These trips don’t stop billion-kwacha contracts that go unaccounted for. They don’t recover funds siphoned from government coffers. They don’t jail those responsible for financial crimes,” Chitera wrote. “Instead, they target villagers—people with little involvement in state-level corruption—turning them into scapegoats while the real thieves are left untouched.”

He condemns the ACB’s approach as a “painful, bitter joke” and questions whether the bureau is afraid to confront high-profile figures or is simply dysfunctional. The message to the ACB is clear: Malawians demand concrete action, not symbolic gestures.

“We want arrests of those who steal millions meant for medicine, for school infrastructure, for rural development,” Chitera concludes. “Enough with the village trips. Start fishing where the real sharks swim.”

For Malawi’s fight against corruption to be credible, the ACB must shift its gaze from remote villages to the power corridors where corruption thrives. Only then will it earn the trust of a nation weary of injustice and empty promises.